How to start your Linux journey

Contents:

This blogpost is an edited version of a post on Tildes which is a “Reddit alternative”.

# Seeing the forest for the trees

So, you want to start using Linux: great! You find out that there are tons of distributions to choose from but you don’t know which one to choose. If you start looking for tutorials, they mostly give you a reccomendation with people then saying that it is bad and you should use something else instead. To help new Linux users out, I thought I would try a different approach: instead of saying which one is good and which ones aren’t, explain a bit about Linux and distro’s so that users understand the landscape enough to make an educated decision.

General disclaimer: this is all my own opinion. Look around, watch videos (The Linux Experiment and Techhut are great Youtube Channels for this) and do your own research. That being said, if you have anything to add or have any questions, I would love to hear them.

Also take a look at Distrochooser. I don’t think all questions are relevant, but it is a good starting point.

# Glossary

FOSS: Fully Open Source Software. Sometimes called Free Software or Open Source Software. Software that is free as in free beer and free as in freedom. Freedom in this context means that users can see how the program works and copy the source code, among other things. FOSS software is also developed by a community of volunteers most of the time. Related terms: OSS, Open Source software, Free Software, Libre software.

# So … what even is Linux exactly?

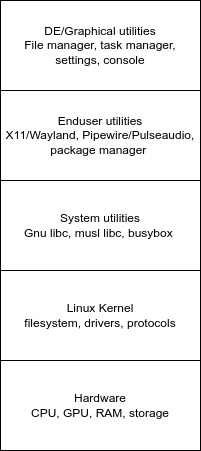

If people talk about “Linux” they mean it as a shorthand for a “Linux distribution” or “distro”. This is an operating system that uses the Linux Kernel. The Linux Kernel is a program that enables a computer to do basic stuff: think reading and writing files, managing RAM, connecting to the internet or Bluetooth and making sure devices like your graphics card and USB-devices actually work. This is important, but with just a kernel there is no easy way for an end user to actually do anything useful on their PC. This is where an ecosystem of programs come in. The first layer above the kernel is system utilities. These provide a set of console commands like gnu libc or musl libc. The next layer is enduser utilities. These are less basic than system utilities and all enable the use of the operating system by an end user. Wayland or X11 enable you to see screens on your computer. Pipewire or Pulseaudio enable you to use audio devices (although the kernel already does some of this through Alsa). The last layer is the final user interface, most often in the form of a Desktop Environment. Window Managers are also an option but they are different enough from Windows and Mac that they are for more advanced users.

The dividing lines might seem arbitrary because they are: in the end all programs work together to make Linux distros work. All operating systems work this way, the only difference with Linux is that it is a collection of separate programs. A DE is the part of a distro that visually sets it apart most: it includes a few more parts but the most important ones are a suite of basic graphical programs like a file manager, a settings program and a task manager. Most of the time, a desktop environment has a larger ecosystem of apps that fit in well with it.

# Choosing a Distribution and Desktop Environment

# TLDR

A distribution and a Desktop Environment are two seperate choices. For Desktops, it comes down to if the goals of the DE align with yours, for distro’s it is a trade-off between stability and ‘cutting-edgeness’.

# Choosing a Desktop Environment (DE)

The main factor when choosing a Desktop Environments is their end goals and vision of what a DE is supposed to be.

I think DEs can be divided in a few categories which follow a certain philosophy:

Curated

“Users use their computer through their DE, so a DE should focus on an easy-to use and streamlined user experience with the apps looking coherent and pleasing.”Lightweight

“Users use a computer for the apps and want them to perform well, thus a DE should use as little system resources as possible.”Tweakable

“Users have different preferences, thus a DE should accommodate tweaking as much as possible so that they can tweak their DE to be just right for them.”Familiar

“Users don’t really care about their DE, they just want to get on with their day. Because of this, a DE should be familiar, and shouldn’t change too much over time.”

Gnome and KDE are the main DEs. They have the following philosophies:

Gnome is a curated distro: Its philosophy is to give a relatively narrow curated experience which is thoroughly tested. Think of it as the MacOS of Linux. An important difference is that it is only similar in user experience, but not in the walled garden way: Gnome is still very much FOSS and community guided.

KDE is a tweakable distro: its philosophy is quite the opposite to Gnome: They believe the end user should be able to tweak a lot about the distro. This does not mean that the default experience is bad (I for one use KDE and have barely tweaked it). It does mean that KDE development is spread out over more code and as a result the experience is less curated and polished (both in UX and bugs) than a more curated distro like Gnome.

Besides KDE and Gnome, there are also XFCE/LXQT and Cinnamon. XFCE (and LXQT) focus on being lightweight and tweakable. The only difference (that I am aware of, I do not know them very well) is that they use different underlying technologies (XFCE uses Gnomes GTK and LXQT uses QT, which KDE also uses).

Cinnamon is mainly bound to Linux Mint (more on distros later) and focuses on stability and familiarity for Windows users.

There are many, many more DEs, but these are the main ones and the ones I would consider first.

# TLDR

DEs can be divided in a few categories roughly in order of popularity (DEs in italic are in multiple):

# Curated

Gnome

Cosmic (POP! OS) Elementary (Elementary OS)

Budgie

# Lightweight

XFCE

LXQT

Mate

# Tweakable

KDE

XFCE

# Familiar

Cinnamon - (Windows)

Zorin-OS - (Windows)

Elementary (Elementary OS - (Mac-OS)

# Choosing a Distribution (Distro)

In a distro, I see the choice mainly as a trade-off spectrum. On one side you have stability and on the other ‘cutting-edgeness’.

A perfectly stable distro is exactly that: stable. A good example is Debian. It uses packages and technologies that have been proven to be reliable. It also only uses very stable versions of these softwares. A side-effect of this is that it is behind on new features. This does not just mean quality-of-life features, but also features like new versions of drivers, which can result in crashes or slowdowns if you apps that require or benefit from up-to-date drivers. The same goes for other software, but this is usually less of an issue.

On the other side is a perfectly cutting edge distro. I think the best example of this is Arch. A cutting-edge distro uses the newest technology stacks (like Wayland) and the newest (main branch) versions of apps. This means that it has the newest features and gets speed ups and new drivers pretty much immediately. This also means that they are the first to experience issues and bugs.

If you have the spectrum I would probably order mainstream distros from stable to cutting edge as follows:

Debian — Ubuntu (or derived, like Kubuntu, Linux Mint etc.) — Fedora (derived, like Norbora) — Arch (or derived, like Endeavor OS, Garuda etc.)

The outlier here is Linux Mint and Ubuntu, because Ubuntu uses a cutting edge technology stack, but a more stable version and Linux Mint uses both older technology stacks and versions.

# General advice

Linux is not difficult to use per-se, but it is different. One of the most important differences is software installation. On Windows, you go online to download a file to install a program. On Linux, this is not the way to go.

An important difference is installing apps

# App installation

Try downloading the app in the app-store first (yes, just like on your phone). 9/10 times, the app will be there. Only if this is not the case, should you go look online. Keep in mind which ‘family’ your distro is a part of. For example: Linux Mint is derived from Ubuntu, which is derived from Debian. This means that you can use an installation file which is labeled as “Ubuntu” or “Debian”.

All this is possible because of package managers: a program that manages all your apps. This includes installing them and keeping them up-to-date. Because Linux is just a collection of programs, like I explained in the first paragraph, all apps use this system, which means that when your operating system is updated, so are your apps. A great advantage is that it means that there is less danger of malware, because you can just use the app store. It also means your apps will stay up-to-date.

One problem with package managers is that proprietary apps (non-foss) apps cannot use the system because it is part of the OS. It is also a lot of work for developers to package all the apps for all distribution families.

A new development which brings a solution is the Portals standard. The two main implementations are Flatpak and Snap. The idea behind Portals is that apps are isolated, so that an app can run on any distro. It also means that they can also access less of the system and have to work with permissions. These work like old Android permissions: developers specify the permissions they need and they always get granted. A sidenote: I greatly prefer Flatpak over Snap. The reason is that Snap uses closed source servers, where Flatpak is fully open source. Flatpak vs Snap is an ongoing debate in the debate in the Linux community but Flatpak seems to be the defacto standard on most distros.

With Portals and the package manager, you can install most apps out of the box, even closed source ones. Chrome, Jetbrains IDES, Steam, Discord, VS Code, OBS and Spotify all have Linux versions. Combine this with webapps with Netflix, Whatsapp and Teams and most people will find that they can use Linux without much problems.

# Home/Office use

So, what if I use my computer mainly to surf the web and edit documents? The DE choice is all personal preference. For the distro choice, anything can work. The thing is: for home use you do not need cutting edge software. This means that for beginners, it is better to stick to more stable distros. Debian is a good choice but may be a bit far behind for most users. My general recommendation is thus Linux Mint because it is stable and most importantly very familiar to Windows users.

# Alternatives to Windows apps for home use

Most home users have some problems with finding Linux versions for some apps they need to use. Some apps don’t have a one-on-one replacement, but some come quite close.

If you need an alternative to any other app, take a look at the excellent Alternative To. You can filter on Linux (and open source).

# Word (Office Suites)

Microsoft Office (Word, Excel etc.) does not work on Linux. At least, not the full app. You have several alternatives.

The first is Office Online. This would be the easiest transition, because it is most similar to the full apps. It does miss some features though. I also find it can be quite sluggish.

Google Docs is pretty snappy and generally works well. Of course, it is closed source and pretty terrible privacy-wise, but if you are writing some school essays, that may not matter too much.

As for FOSS alternatives, you have Libreoffice and OnlyOffice. Libreoffice is more feature-complete but Docx support can be hit or miss. Onlyoffice has great Docx support, but has less features. If I had to recommend one, I would go for OnlyOffice.

You can also consider using Markdown, Latex. The advantage here is that there are tons of options. Next to that, I love the fact that I can focus on writing first and worry about layout later and have a consistent document in the end. I use Markdown a lot: this blog is written in it, I use it for notes, essays and presentations. I especially like using Joplin for note-taking and prefer it a lot over any WYSIWYG editors like Word now. I have also heard good things about Obsidian. Besides that, I am keeping an eye on the developments at Typst because it hits a sweet-spot for me personally. It is sadly still in Alpha, so nowhere close to ready for general use.

Disclaimer: I do not often use photo editing or video editing software, but I have written down everything I know from what I have heard

# Adobe Photoshop (Photo Editing)

Photoshop (or any Creative Cloud app) does not work on Linux. That being said, Adobe is developing a webversion, although it is in the early stages and therefore quite limited. Photopea is an online Photoshop clone which I have heard a lot of good things about.

Gimp is always an option, although the interface can be intimidating.

I’ve heard that Krita can work well for digital drawing.

# Adobe AfterEffects / Sony Vegas (Video Editing)

Kdenlive is by far the most complete FOSS video editor on Linux.

Davinci Resolve is a paid (non-FOSS) option which supposedly works well.

For light editing (think Moviemaker), there are tons of apps. I personally sometimes use Openshot which reminds me of Moviemaker. Shotcut seems to be a good Sony Vegas alternative.

# Gaming

So what do you need to look out for in gaming? Well,gaming greatly benefits from recent drivers and software. Because of this, I would not recommend Debian. Besides that, it comes down to personal preference. Arch will work but can be dauting to beginners. I personally use Fedora because I like it has a leading edge technology stack, but uses stable versions.

If you like Fedora, I would personally go for Norbora because it has gaming-specific optimisations made by a well known Proton developer: Glorious Eggroll.

If you go for Ubuntu derivatives, I would advice against Linux Mint, because it is behind on their tech-stack. This is an advantage for home-use but a disadvantage for gaming. Other Ubuntu derivatives will work fine for gaming. POP! OS is especially for gaming, because it includes things like the official NVIDIA-drivers by default

If you want to try Arch, just Arch is fine (maybe using the new Archinstall). If you want a GUI installer you can look into Garuda Linux or EndeavorOS. Whatever you do, do not install Manjaro.

# Steam

I could write a whole essay about Steam (Yes, even larger than this one), but there are already many videos about the subject online, so I will try to keep it brief. The important bit is that Valve (the company behind Steam) has released the Steam Deck, as you might know. The Steam Deck uses desktop Linux, so Desktop Linux has piggy backed a lot of Valves work for the Steamdeck.

An especially useful piis Proton (derived from Wine) which allows Windows games to run on Linux. To see if your game works, take a look at Protondb. You can even log in with Steam (don’t worry, it is a FOSS project) to see what part of your library works. Most games work except…

# Multiplayer games and Anticheat

Multiplayer games are hit or miss on Linux for a simple reason: anticheat. Most anticheat software have Linux versions and even work with Proton, but developers block it out of fear for cheaters. This fear has never really been proven and there are easier ways of cheating than through Wine, but I digress. The end-result is that some games do not work on Linux, or might ban you players for using Proton.

# Other launchers

Launchers beside Steam are not officially supported, but there are solutions: you can still use Proton with them though with FOSS clients. Examples are Lutris and Bottles for multiple launchers, and Heroic for GOG and Epic Games. PlayOnLinux is considered outdated and has de-facto been replaced with Bottles.

# Conclusion

The Linux desktop is great: it gives you freedom to do what you want and it is made by users for users. This means you get to be part of an amazing community of developers and users who care about free software, privacy and user-friendlyness. I hope this guide helped you on your Linux journey and in the words of Louis Rossmann: I hope you learned something.

PS: These were the songs I was listening to during the making of this post.